Elite performers need skill, talent, and practice. They also need the mental toughness that can be learned through performance psychology. A key part of this mental toughness is about how to achieve high performance under pressure.

The pressure of high performance

Elite performers frequently face critical tasks in which failure would be disastrous. Consider an elite surgeon – she starts a life or death surgery and must stay focused and in peak form for long stretches of time. She can’t take a break for a snack or to watch cat videos. During surgery, she must manage pressure and stay focused or the patient could die.

High pressure situations are not always life or death, but they often rely on perfect performance at one key moment. Elite athletes train relentlessly for years. Those years of training might all come to rest on their performance at one Olympics or in one race or in one competition. Executives make decisions that could cost millions of dollars or lead to layoffs or public ridicule.

Yerkes-Dodson law of high performance

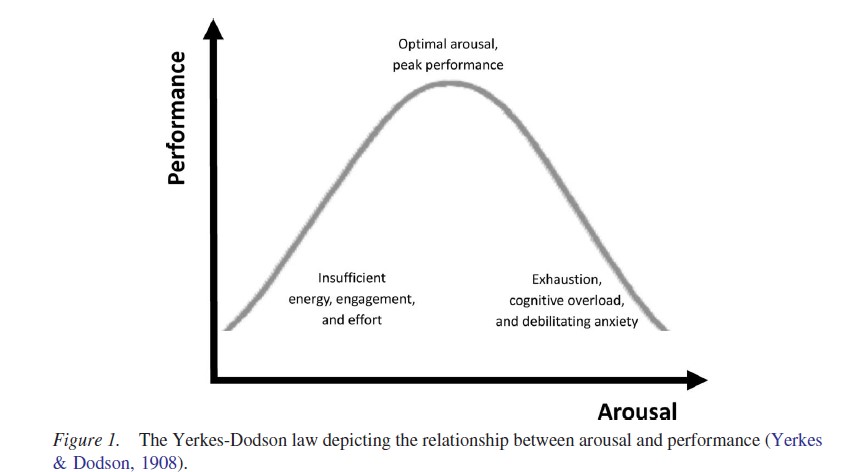

Continuing the discussion of high performance in the Consulting Psychology Journal, Rob Kaiser wrote “Stargazing: Everyday Lessons from coaching elite performers”. Kaiser points to a key principle in psychology called the Yerkes-Dodson law that explains performance under pressure.

The Yerkes-Dodson law shows that there is an optimal point of pressure (or arousal) to achieve peak performance. Too little pressure leads to lower levels of performance. Too much pressure also leads to lower levels of pressure. Instead, you want just the right amount.

Threat versus Challenge Appraisal

Part of the Yerkes-Dodson law has a biological basis. People physically react differently based on how they perceive the high performance task. If the task seems impossible and they feel likely to fail, the person sees this as a threat. When a person feels threatened, the body reacts with faster heartbeats and the release of the stress hormone cortisol. Blood pressure rises, breathing gets shallower and sweating starts.

If the person feels prepared for the challenge, the body reacts more positively. Positive reaction involves the release of adrenaline and increased blood flow which physically prepares the person for the task.

Prepare mentally to see challenges

Performance Psychology supports elite performers in terms of their mental preparation. Mental toughness can help them approach the situation calmly and see it as a challenge – not a threat. The challenge mode puts the elite performer into the optimal mode of moderate arousal. According to the Yerkes-Dodson law, this moderate arousal sets the stage for higher performance.

As with charisma and transformational leadership, research continues to show us that moderate amounts of something is often more effective than too much or too little.

Illustration of the Yerkes-Dodson law

At the far left of this graphic, pressure (arousal) is low and performance is low as well. This state reflects low levels of energy, engagement and effort. On the far right, too much pressure also results in low performance. The excess pressure cause exhaustion, overwhelm and crippling anxiety. The optimal spot shows up in the middle of the curve – performance is high with the right amount of pressure.

The three summer interns and the optimal level of pressure

Although the Yerkes-Dodson law might seem intellectual and intimidating, it is really quite simple. I saw a clear demonstration one year with three summer interns. Our company sponsored about 20 college-level interns for the summer across a variety of functions. As their capstone experience, the interns each did a presentation at the end of the summer to highlight their project. The capstone presentations were attended by other interns and also by their supervisors and the vice presidents for their functions.

These presentations provided an opportunity to share and shine. Successful interns received offers for full-time jobs.

Since I oversaw the intern program, I had a front row seat to watching them prepare for the presentations. Three interns from the IT group displayed the different elements of the Yerkes-Dodson law. All three completed solid summer projects, but they showed up quite differently in the presentations.

Intern 1: Not enough pressure

The first intern downplayed the importance of the presentation. He put minimal energy into preparation and did not practice at all. He showed up late dressed in rumpled clothing. During his capstone presentation, he rambled, did not credit people who supported him and forgot to make his key point about cost savings. Intern One felt no pressure and performed poorly.

Intern 2: Too much pressure

Intern Two felt too much pressure and struggled for different reasons – practically radiating anxiety about the presentation. While preparing, she was fixated on every word on every page. She spent countless hour rehearsing. On presentation day, she seemed wired and brittle and stressed. She made it through the presentation and said all of the right words, but her anxiety overshadowed the message.

Intern 3: Just the right amount of pressure

Intern Three found the right balance. She accepted the presentation as a challenge and an opportunity – without mentally building it into a life or death moment. She prepared and practiced, but also infused the presentation with some extemporaneous comments and humor. The professional, yet relaxed, presentation highlighted her project and showcased her abilities.

You might be relieved to know that all three interns received job offers. The presentations provided a great learning opportunity for them – and that is the point of summer internships.

But moments like that make a difference. Intern Three already started to differentiate herself from the other interns. That kind of positive attention gets people on the radar screen with senior leaders and talent management professionals. All three got job offers. Intern Three also made the “high-potential” list that gave her priority for future developmental opportunities.

References

Kaiser, R. B. (2019). Stargazing: Everyday lessons from coaching elite performers. Consulting Psychology Journal, 74, 2, 130-139. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000143

Yerkes, R. M., & Dodson, J. D. (1908). The relationship of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology, 18, 459–482. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cne.920180503

Rob Kaiser, Kaiser Leadership Solutions

Rob Kaiser also conducted the research highlighted in the Dark Side of Charisma article.